By Jon Ford, Managing Director of Global Government Services & Insider Threats and Tim Appleby, Managing Director of US Federal Programs and Services at Mandiant

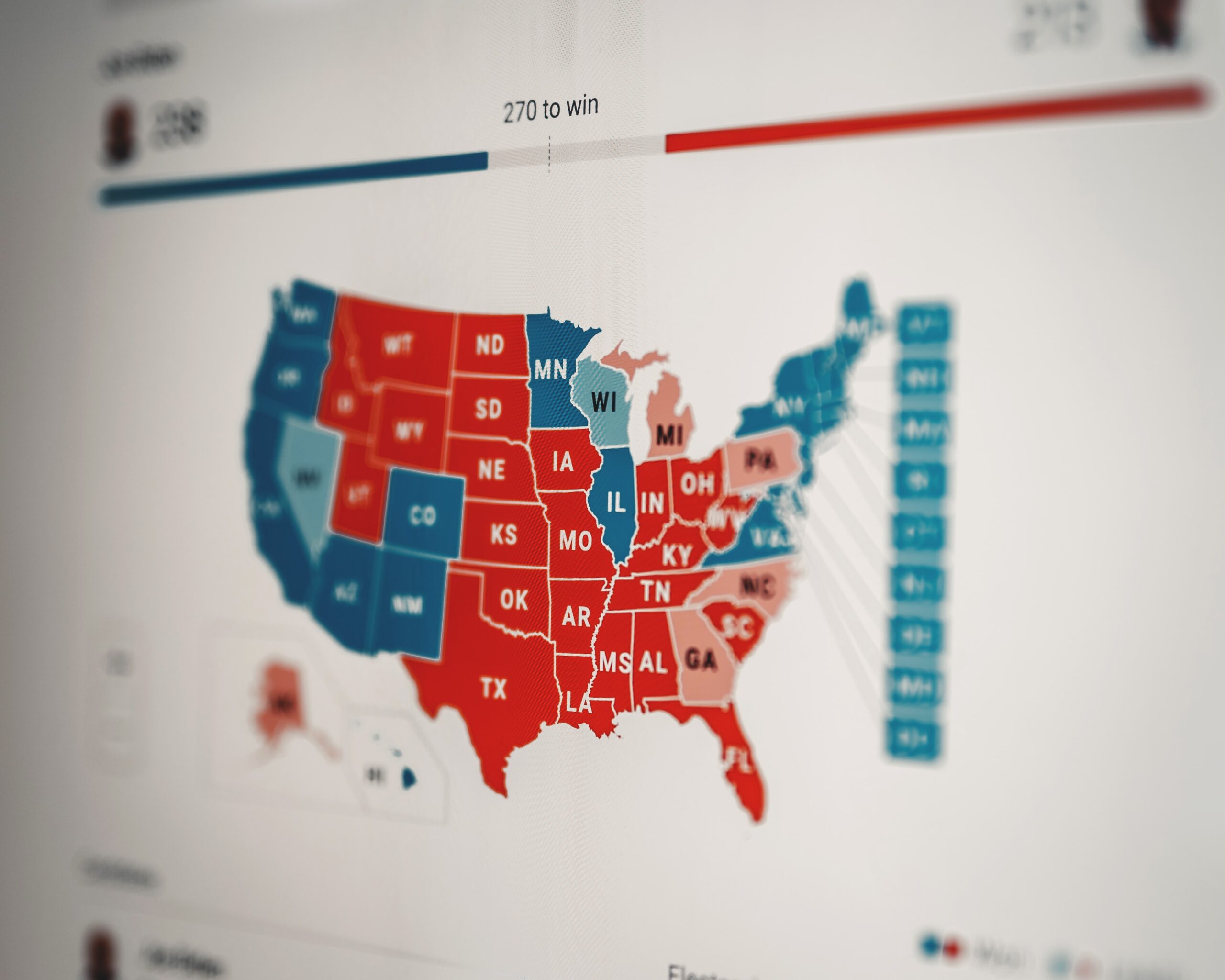

Elections in the United States have become increasingly polarized, with many Americans losing trust in the voting process and results, according to the Pew Research Center.

This trust has been eroded due to multiple factors, such as: how ballots are cast and processed; questions around the expertise of election workers; and the rise of cyberthreats against government infrastructure and systems.

The latter issue is particularly complex. Securing the individuals, organizations, and infrastructure involved in elections from malicious cyber activity is a challenge. We live and work amid an ever-evolving threat landscape, and the number of threat actors continues to grow.

More specifically, the scope of threats are now much wider than ever before — be they unintentional or malicious insiders, trusted third party suppliers, social and media outlets, or well-funded state-sponsored threat groups. These threats encompass all aspects of the election ecosystem, from the technology and operational processes down to the voters and candidates themselves. In addition, attackers use a variety of methods such as social engineering efforts, ransomware, and disinformation campaigns to achieve their end goal.

The particular reasons for why a threat actor might target a specific election vary widely, and their motivations stem from both sides of the partisan divide. For example, Mandiant observed that Iranian actors impersonated the Proud Boys organization to send threatening emails to voters in Florida during the 2020 US presidential election. Each new election cycle can bring new threat activity, in many cases maturing the successful tactics used by their predecessors during past election cycles.

So, how do we begin to rebuild election trust? It starts with a holistic approach that includes supply-chain risk management, embracing a zero trust philosophy, and insider threat management.

Supply-chain risk management

In the past, supply chain risks to elections revolved around ballot availability, voting locations, and personnel to facilitate voting. For example, during the pandemic the influx of mail-in ballots threatened the supply of paper ballots. Integrity was maintained through physical controls that could be readily cataloged and captured through two-person integrity and other commands.

Today, new complications arise with the move toward electronic ballots and voting systems. These new technologies bring rise to new targets and attack methods providing opportunities of scale and speed because of the ways these systems are interconnected.

Election security now must extend beyond purely technological controls or solutions. This requires completely rethinking how and why we do everything and ensuring it is adequately documented and repeatable. This also requires a merger in thinking, not only looking at the technological solution, but the human aspects of the risk, taking into account behaviors, motivations, and social norms.

In light of these supply-chain risks, the main objective is to build a close relationship with vendors and together work to reduce any risk that may directly impact the elections. This can be an expensive and time-consuming endeavor, but it’s very necessary. This becomes apparent when considering the SolarWinds supply chain attack. With this in mind, it is highly recommended that a supply-chain risk management framework be implemented to ensure a consistent and repeatable process is followed. This framework should be a continuous cycle that takes into account:

- Vendor inventory and risk ranking

- Vendor profile

- Management support

- Vendor’s regulatory compliance

- Vendor’s information gathering

- Vendor’s insider threat risk management

- Vendor’s supplier risk management

- Vendor’s information security best practices

- Continuous vendor assessments

Zero trust philosophy

Zero trust principles should be a baseline for election security. Overall, the philosophy can be summarized as “never trust, always verify.” Zero trust encompasses identities, devices, networks, applications, and data. Cross-mapping these components to our electoral infrastructure can provide a more trustworthy electoral process:

- Identity: Often, our first thoughts are of voter identity, but in this case, voters are only one part of an election. Vendors, contractors, and other entities are responsible for setting up, orchestrating, and supporting the election process. We need to verify the identities of and responsibilities of each group to ensure their roles are properly protected.

- Devices: Devices include any physical or virtual infrastructure that supports the election process — including voting machines, tabulators, servers, and workstations. It is critical for election integrity that there is no tampering or missing equipment. An inventory of all devices, as well as a chain of custody, should be established and regularly updated and reviewed. Endpoint detection and response technologies should also be implemented.

- Networks: Networks refer to how we interconnect devices to transmit electoral data before, during, and after an election. By implementing “never trust, always verify” zero trust principles to networks, we can ensure environmental isolation of electoral components. In addition, network traffic should be encrypted.

- Applications: These include the applications, software, and firmware running on all devices used to support elections. There should be a software supply-chain process to ensure that only approved and validated applications and firmware are used. Also, check that third-party security testing has been performed on all electoral systems.

- Data: This refers to any data used during the electoral process; it may be voter information, ballot data, voting results, etc. Data needs to be adequately safeguarded from tampering or disclosure; it should be categorized and security controls implemented based on those categories; access should only be provided on a need-to-know basis and that access should be audited, logged, and monitored.

This may seem like a lengthy process, yet all of these components are required to build a chain of trust for successful elections. Any failure in this chain of trust can result in an election-wide failure. Trust is essential and requires that we verify every detail.

[For more information on zero trust architecture, check out the recent blog series from the Cybersecurity Tech Accord].

Insider threat management

By definition, an insider threat is anyone to whom authorized access is granted who then uses that access to harm the organization. This is as true for elections as in any other sector. In one recent example, a Colorado judge in 2021 barred an elected county official from supervising any future elections after it came to light that she had allowed a man not affiliated with the election commission to photograph and publish confidential voting-machine passwords, as well as to make copies of the hard drives and change settings on the machine that introduced security vulnerabilities into the process.

Unfortunately, the Colorado example is not an isolated event. Similar incidents have occurred in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Ohio.

There are two main categories of insider threats:

- Intentional: Malicious actions taken due to a personal belief or grievance, ambition, or financial pressures. Sometimes it involves collusion among insiders and external threat actors to compromise the electoral process.

- Unintentional: Risks created due to carelessness or disregard of rules or policies.

Insider risks cannot be eliminated altogether; we can only seek to mitigate them to a level that protects the electoral process and the staff supporting it. This requires a formal insider risk management program leveraging a holistic approach incorporating components of governance, data protection, zero trust, chain of custody, access control, and proper documentation.

For unintentional insider threats, we can reduce risk by providing proper training, documentation, and controls for all procedures of the electoral process. It’s also valuable to keep a keen eye on the behavior and attitude of the electoral staff, as some negligent actions can be witnessed by others and corrected in a timely fashion.

To address intentional insider threats, however, it is vital to understand the motivations of the individuals that pose a threat — such as monetary gain, need for recognition, attention-seeking, and a distorted image of right and wrong. These motivations may lead electoral staff to collude between them or with third parties, which can cause harm through spreading dis-misinformation or mal-information, or even breaking physical security protocols that can pollute or tamper with electoral data.

These threats are significant enough that managing them must be a daily task for election officials, requiring constant review.

Conclusion

We must continue to protect the integrity and trust in elections by first recognizing the inherent challenges and need for holistic, system-wide solutions. However, by investing in tools and partnerships, federal, state, municipal and tribal governments can better defend against attacks on democracy.

Mandiant and others in industry help government authorities understand risk types and develop the appropriate controls to mitigate them in order to maintain election integrity. Ultimately, democracies must have trust their election processes, which means they must be secured.